Census citizenship question could transform Texas elections

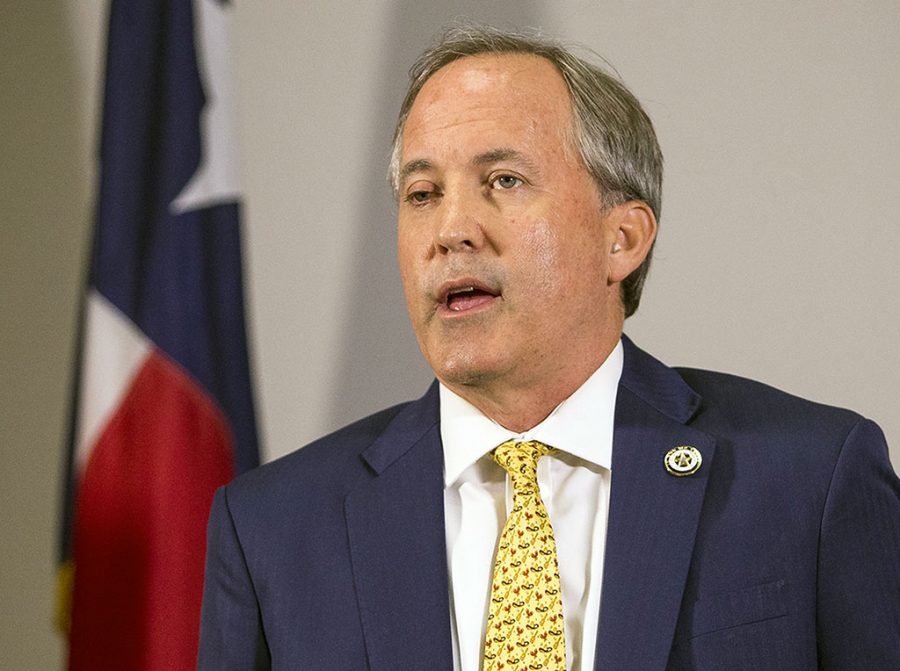

Nick Wagner/Austin American-Statesman

Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton speaks at a news conference May 1, 2018, in Austin, Texas. Computer files discovered in the home of Tom Hofeller, a Republican operative who died last year, contain a blueprint for how the GOP could extend its domination of legislatures in states where growing Latino populations favor Democrats and offer compelling context about a related case currently before the U.S. Supreme Court. Many of the state’s top Republicans, including Paxton, have publicly expressed support for a citizenship question on the Census.

June 1, 2019

AUSTIN, Texas — Computer files discovered in the home of a Republican operative who died last year contain a blueprint for how the GOP could extend its domination of legislatures in states where growing Latino populations favor Democrats and offer compelling context about a related case currently before the U.S. Supreme Court.

The files from North Carolina redistricting expert Tom Hofeller include detailed calculations that lay out gains Republicans would see in Texas by basing legislative districts on the number of voting-age citizens rather than the total population. But he said that would be possible only if the Census asked every household about its members’ immigration status for the first time since 1950.

The U.S. Supreme Court is expected to rule on that question as early as next month. But Republicans who support adding the citizenship question have rarely acknowledged any partisan political motive. The emergence of the documents now could figure heavily in the case the court is considering.

To civil liberties lawyers suing to block the question, it’s now clear that partisan politics were at work all along. They assert in court filings that Hofeller not only laid out the political benefit for the GOP but also ghost-wrote a U.S. Department of Justice letter calling on the Census Bureau to add an immigration question to next year’s survey.

The Justice Department denied the allegations in a statement on Thursday, saying Hofeller’s Texas analysis “played no role in the Department’s December 2017 request to reinstate a citizenship question to the 2020 decennial census.” In that 2017 letter, Justice said it needed citizenship information to protect the voting rights of minorities.

The U.S. Supreme Court heard arguments on the citizenship question in April and is expected to rule by July whether it will be allowed.

“What it would result in is outrageously overpopulated and underpopulated districts,” said Matt Angle, a Democratic redistricting strategist, adding that the resulting maps would harm Texas’ booming Hispanic population with the aim of benefiting Republicans.

Many of the state’s top Republicans, including Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton , have publicly expressed support for a citizenship question on the Census. On Friday, Texas Gov. Greg Abbott’s office did not respond to questions about whether he would endorse using citizenship data to draw new maps, although a spokeswoman said last year that the Census question would provide greater transparency and was dismissive of fears of under-reporting.

Opponents contend that many noncitizens and their relatives will shy away from being counted, fearing that law enforcement will be told of individuals’ citizenship status. That could cause undercounts in places with large Latino populations, including parts of Texas, California, Florida and Arizona, and could cost them seats in Congress as well as federal funding.

But the political impact of the citizenship question could go beyond an undercount if states use citizenship information to draw the maps for state legislative districts. The concept was introduced in legislation over the last few years in Missouri and Nebraska, where the state constitution already calls for excluding “aliens” from its apportionment. And Alabama has sued the federal government saying it should supply citizenship information.

In Texas, Hofeller calculated in his report that about a half-dozen Latino-dominated districts would disappear, including a portion of one in the Dallas area, up to two in Houston’s Harris County and two or three in the border counties of South Texas. “A switch to the use of citizen voting age population as the redistricting population base for redistricting would be advantageous to Republicans and Non-Hispanic Whites,” he wrote.

There’s a question of whether the switch would be legal.

The U.S. Constitution specifies that congressional districts should be based on how many people — not citizens — live there. But it’s murkier for many state legislative districts.

The case at the heart of Hofeller’s 2015 report was brought by Texas voters who contended it was unfair that noncitizens and minors were counted in making legislative districts because it gave a bigger voice to a smaller number of eligible voters in places with a lot of noncitizens and children. In response, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 2016 that states could not be forced to use voting-age citizens as the basis for districting.

Justice Clarence Thomas agreed with that decision but wrote a separate opinion that seems to invite states to do it on their own. “It instead leaves states significant leeway in apportioning their own districts to equalize total population, to equalize eligible voters, or to promote any other principle consistent with a republican form of government,” Thomas wrote.

If a state tried to use a limited population count for redistricting, a lawsuit would be likely.

“They’re always trying to argue that only citizens should be counted for drawing the lines. They think it’s to their advantage,” said Luis Vera, a San Antonio-based lawyer for the League of United Latin American Citizens who has spent decades in court with the state over redistricting battles and said he’d sue if Texas switched to citizen-based districts.

Justin Levitt, a constitutional law professor at Loyola Law School in Los Angeles, said lawmakers may be reluctant to change which count is used for redistricting knowing they’d face legal challenges.

He said that even if a switch could be approved under a state constitution, it could run afoul of the federal Voting Rights Act, which bars state and local governments from restricting equal voting access based on race.

But Rogelio Sáenz, a sociologist at the University of Texas-San Antonio, said he expects it will be considered in Texas, where Democrats picked up 12 seats in the House last year, now giving them 67 of the 150.

“The Republican Party is really anxious to gain back those few seats they lost in the last election,” Sáenz said.