Tiananmen: When China shifted from solidarity to stability

June 3, 2019

Thirty years since the Tiananmen Square protests, China’s economy has catapulted up the world rankings. Yet political repression is harsher than ever.

While hundreds of thousands of Muslims are held in reeducation camps without charge, student activists face relentless harassment, and leaders in the beleaguered dissident community have been locked up or simply vanished.

It’s a far cry from the hopes of the idealistic student demonstrators, and a level of control far beyond what many imagined possible, even after the army’s bloody crushing of the protests on the nights of June 3-4, 1989. Critics say the Tiananmen crackdown, which left hundreds, possibly thousands, dead, set the ruling Communist Party on its present course of ruthless suppression, summary incarceration and the frequent use of violence against opponents in the name of “stability maintenance.”

Chinese officials routinely respond to questions about the suppression by pointing to the economic progress China has made. In the three decades since the protests, China has risen to become the world’s second-largest economy and is forging ahead in areas from high-speed rail to artificial intelligence and 5G mobile communications.

While the Tiananmen protests ushered in the era of new party leader Jiang Zemin under which the economy grew, corruption also became endemic and faith in communism was exhausted, essentially finishing off what the violent, radical Cultural Revolution had begun almost 20 years earlier, said Zhang Lifan, who was a scholar at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences in 1989.

“The moment the government ordered its army to fire on its own people, it lost its legitimacy,” said Rowena Xiaoqing He, a former protester who created a course on Tiananmen at Harvard and is a current member of the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton.

Despite the setback it dealt to Chinese political reform, the Tiananmen crackdown may have had a salutary effect on events elsewhere, hurrying the peaceful fall of the Berlin Wall the same year and the dissolution of the Soviet Union soon after, said Zhang, the scholar.

“So even though the Chinese people didn’t benefit from it, the rest of the world felt the impact,” he said.

A nation scrubbed of truth

CLAREMONT, Calif. — The young woman lay on a mat in the concrete hallway of a Beijing hospital on June 4, 1989. She weakly held up an X-ray showing a bullet in her shoulder. Knowing I was a journalist, she whispered something I had heard numerous times in the previous three weeks: “Report the truth.”

People hold Chinese national flags leave Tiananmen Square after attending the daily flag raising ceremony on the 30th anniversary for the 1989 crackdown on pro-democracy protest in Beijing, Tuesday, June 4, 2019.

She was among the tens and possibly hundreds of thousands of people on the streets of Beijing when soldiers from the People’s Liberation Army shot their way through the heart of the Chinese capital and retook Tiananmen Square, the nexus of nationwide protests seeking social freedom and democracy.

The crackdown 30 years ago Tuesday stopped in its tracks a slow opening to the world that senior leader Deng Xiaoping had launched a decade earlier. The U.S. and China formalized diplomatic ties in 1979, and reporting from China in the 1980s, I had written about investment and expansion by Disney, Coca-Cola and Kentucky Fried Chicken.

Foreign investment eventually returned and economic reforms continued, but a fundamental political change settled on China in the wake of Tiananmen, said Wang Chaohua, who in 1989 was a graduate student and No. 14 on a most-wanted list of 21 fugitives published by the government in the weeks after June 4.

“Before 1989 the official slogan was ‘anding tuanjie’ (peaceful solidarity),” Wang told me last week. “After the crackdown Deng emphasized ‘wending yadaoyiqie’ (stability over all else). The new slogan was no longer speaking to society, but to the (Communist) Party. . And the roots are in Tiananmen.”

The story of China’s economic success is familiar. When I returned to China as a correspondent from 2010-2013, Chinese brands such as Baidu, Alibaba and Huawei were expanding aggressively overseas, and Apple, Nike, Nestle, Toyota and Mercedes-Benz were turning China into a critical market.

For a foreign correspondent, there was far more access to information than in the 1980s. All ministries had spokespeople, albeit often elusive, and statistics were abundant, albeit often suspect.

But the government also tracked down and sent away reporters who went to Tibetan Buddhist areas of Sichuan province after a wave of self-immolation protests, and blocked the websites of major western media, as well as Gmail, Whatsapp, Reddit, Tumblr and Pinterest and a host of others.

That pattern continues today in far-west Xinjiang, where authorities disrupt foreign journalists’ attempts to report on the re-education camps that have sprung up, housing up to an estimated million ethnic Uighurs.

This clampdown on information can be traced in large part to the government’s failure to stop the news flow from the hundreds of journalists covering the Tiananmen protests in 1989. It was only at the end that authorities moved against journalists en masse.

As I went back to the Beijing Hotel to file updates and radio reports on the night of June 3, a plainclothes security official and three uniformed officers confiscated one of my videocassettes, filled with two hours of footage from the previous several days. They had been waiting in the empty lobby, picking off journalists as they came in.

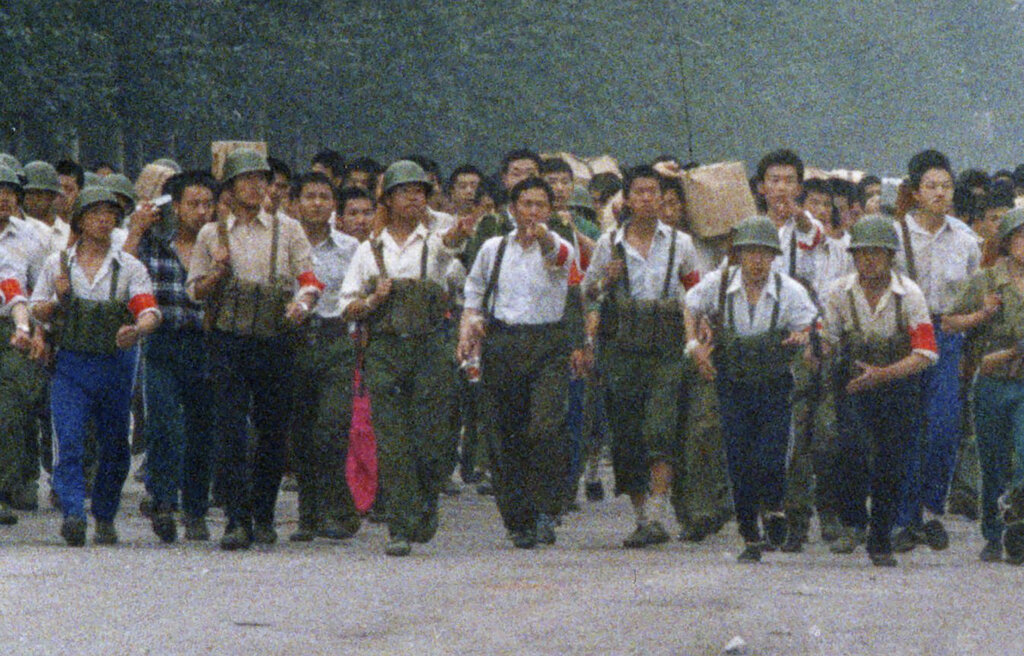

In this June 7, 1989, file photo, Chinese troops keep a sharp eye out as their truck makes a momentary stop on Changan Blvd in Beijing, China.

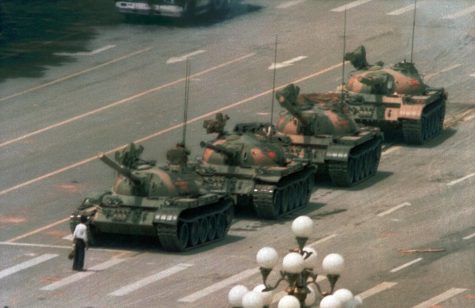

I was outside the hotel on June 5 when I saw people ducking and running toward me ahead of approaching tanks. I took one shot before hustling upstairs for a better view. It was only weeks or months later that I printed the photo and discovered the man who had stood in front of the tanks in what would become an iconic image of Tiananmen. My photo showed him waiting in apparent calm, moments before the confrontation.

The next day, I was — foolishly — taking photos of a column of soldiers marching straight at me. A commander barked orders while pointing at me, and two soldiers, their eyes on me, started running in my direction. I turned and ran, and heard two shots. Dropping to my knees behind a minivan, I furiously unwound my film, hid it in my sock, and waited for the soldiers to come.

They never did, and when I peeked under the van, I saw them walking away. After the column had marched past, I crossed a parking lot, hopped a wall and retrieved a bicycle I had borrowed. A group of onlookers, who had watched everything, burst into applause when they saw me.

In the ensuing years, the Chinese government has scrubbed virtually all mentions of the protests from textbooks, the media and the internet. Meaningful political reform seems unlikely as today’s leader, President Xi Jinping, tightens his hold on power. And a commitment to transparency and accountability still seems a distant possibility. Only when that happens, though, will most Chinese learn the truth.

‘Tank man’ photographer urges China to open up on Tiananmen

In this June 5, 1989, file photo, a Chinese man stands alone to block a line of tanks heading east on Beijing’s Changan Blvd. in Tiananmen Square.

ALHAMBRA, Calif. — The American photographer who shot the iconic image of a man standing in front of tanks at the 1989 Tiananmen protests says it’s time for the Chinese government to come clean about the bloody events of 30 years ago.

Jeff Widener was an Associated Press photo editor based in Bangkok when he was called in to help cover a growing student-led pro-democracy movement centered on Beijing’s Tiananmen Square.

The day after the military crushed the protests on June 3-4, Widener took the shot of an unknown man holding shopping bags facing a row of tanks. The photo of “tank man” became one of the most famous images of defiance of the 20th century.

In an interview, Widener said he doesn’t understand why China’s leaders won’t admit to errors made and reveal the truth behind the crackdown.

“The United States and European countries have made mistakes throughout history and they’ve reconciled those problems,” Widener told AP.

“I think it’s time for China to move forward and just come clean on what happened, report to the family members what happened to their loved ones so that they can put this to rest,” he said. “I think that’s the right, decent thing to do.”

The 62-year-old Californian developed a love of photography at a young age, eventually joining AP as Southeast Asia picture editor.

Rejected for a journalist visa at the Chinese Consulate in Bangkok, he flew to Hong Kong, where he got a tourist visa through a travel agency, and made it through customs in Beijing with a mobile darkroom in his luggage.

With the protests in full swing, he developed a daily routine of riding a bicycle early in the morning to Tiananmen Square, where thousands of students were camped out.

His May 30, 1989, photo captured the “Goddess of Democracy,” the students’ version of the Statue of Liberty, facing the portrait of Communist China’s first leader, Mao Zedong, on the massive Tiananmen gate.

In this June 7, 1989 photo, Chinese troops patrol the street after the Chinese army fought its way into Tiananmen Square the night of June 3-4 to reclaim the square from student-led demonstrators who had been protesting for democratic reforms for three weeks.

“So you had this democracy facing off with Communism that was quite striking,” Widener said.

Soon, the mood began to change. After the government declared martial law, Beijing residents blocked roads to prevent troops — at that time unarmed — from moving toward the square.

That enraged party elders led by China’s paramount leader, Deng Xiaoping, steeling their determination to end the protests by military means.

On the night of June 3, Widener rode to the square with AP reporter Dan Biers, just as the People’s Liberation Army began fighting its way eastward through barricades and crowds of protesters.

He suffered a serious head injury from a flying piece of asphalt, but made it back to the AP bureau and his hotel.

Widener emerged the following afternoon to find rock-strewn streets, burnt-out vehicles and a population dazed by the violence deployed against them by the government.

Asked to get a shot of military forces occupying the square, Widener headed to the Beijing Hotel, which had vantage points close to the action, even as gunfire continued to pop from parts of the city.

There, he met an American college exchange student, Kirk Martsen, who would play a key role in the tank man tale. Martsen acted as if he and Widener were old friends, allowing the photographer to slip past security men guarding the hotel entrance.

A Chinese paramilitary policeman stands guard in front of Mao Zedong’s portrait on Tiananmen Gate on the 30th anniversary of a bloody crackdown of pro-democracy protesters in Beijing on Tuesday, June 4, 2019.

Martsen had a room on the hotel’s sixth floor facing the street, to which he gave Widener access. The problem though, was film. Widener had run out and there was no way to go back to the AP bureau to get more.

Martsen went hunting among the frightened tourists in the lobby, returning two hours later with a single roll that would prove crucial in the events that followed.

Widener stayed overnight, and early on June 5, he rushed to the balcony upon hearing the sound of approaching tanks.

“I started to take a photograph and a guy walks out with shopping bags and I’m thinking to myself, ‘you know this guy’s going to mess up my photograph,” he said. “I mean it really was like I wasn’t thinking clearly.”

“So I just watched him and waited. But they didn’t shoot him. So I thought you know I need a closer shot,” he said.

The man moved at least twice to block the tanks and climbed on the turret of one to converse with a crew member. Eventually, he was whisked from the scene by two men in blue, whose identities, like that of the man himself, have never been revealed.

At least five photographers as well as videographers shot the scene, but Widener’s version became by far the most famous. The photo made him a Pulitzer Prize finalist and was named by Time magazine as one of the 100 most influential images of all time.